In the 237 summers which have come and gone since July 4th, 1776, the date has increasingly become a juncture for white sales and auto dealer blowouts. In fact, lost amidst the mall madness and car lot carnivals is a simultaneously fascinating and pedantic period of committee meetings, assignations, rewrites, copies, messengers, vote-taking and gallons of coffee, ale and wine. As I currently scribe the fourth novel in my six-part, historical-fiction series of books, Savannah of Williamsburg, Independence Day takes on a more front-and-center appearance than usual as research takes me through the 1750s, well into the meaty burgeoning of colonial revolution.

Even as I contemplate the importance and sacrifice involved with 237 years of sovereignty, I still can't help but fret over whether my red-white-and-blue argyle, Brooks Brothers ankle-socks will look fabulously Gatsby, or just clash with my red-white-and-blue striped, Unisa sailing pumps and the polka dot dress I've selected for my own Fourth of July pool party. Sure, the Fourth has vaguely patriotic elements incorporated into contemporary festivities, including fun, over-the-top, nationalistic fashion and cheesy, throw-away, dutiful décor at park picnics, beach BBQs and backyard pool parties countrywide. Still, maybe the best accessories and décor of all would be rolled up bits of parchment, feather quills and some sturdy, pewter tankards. Funny enough, I actually have all those things ... in multiples.

As King George III whiled away the time with amateur astronomy and overseeing his vast acreage of crops at Windsor Castle (hence the moniker "Farmer George"), he also spent a great deal of time making proclamations and conjuring new tax revenues for his rowdy, naughty, Americans across the Atlantic. Revenues were vital to the British coffers in the mid- to late-18thC., much needed to recover from the Seven Years' War (a.k.a. The French and Indian War) and various scuffles elsewhere with Spain and France. Who better to help pay than the beneficiaries of, in particular, all that French fighting in the forests of the Seven Years' War? Hence, the Stamp Act, the Townshend duties and more. By June of 1776, the original Thirteen Colonies had enough. Enter, Richard Henry Lee et al.

On June 7, 1776, Virginia representative Richard Henry Lee introduced his Lee Resolution to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Lee, an early member of the still-influential Virginia/Ohio/Maryland/Pennsylvania family dynasty, was a descendant of Richard Lee I: a.k.a. "The Immigrant", coming to Jamestowne Island in 1639, and making a fortune farming, curing and selling to England, Virginia tobacco. Representative Lee was also descended from Thomas Lee, founder of the Ohio Company; and, would become an ancestor to famed Civil War Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Instructed by the Virginia Convention, Lee crafted and drafted a three-part proposal for colonial independence in America: a declaration of independence, a call to form foreign alliances, and a plan for confederation. In response, on June 10, 1776, Congress appoints three committees, one to address each component. The Declaration of Independence is the big bit we know best.

The committee to draft the Declaration of Independence was comprised of five men, representing all regions of the original Thirteen Colonies: John Adams of Massachusetts and Roger Sherman of Connecticut (representing New England); Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and Robert R. Livingston of New York (representing the Middle Colonies); Thomas Jefferson of Virginia (representing the South). The tall, quiet, scholarly redhead from Virginia was tasked with the actual writing of the Declaration, as Adams claimed Jefferson the one best possessing "the happy talent of composition".

Jefferson spent the next seventeen days, June 11-28, drafting the first version of our Declaration. He then passed it over to Adams and Franklin, whom offered suggestions and tweaked some phrasing. (Thought: As a writer, I've oft wondered how that scene played? Writers, no matter how magnanimous or altruistic, don't really appreciate constructive criticism. "Which words should I change?" will always be asked with a polite, tight smile, unblinking, wide eyes and just a touch of acid. Go ahead. Try it with a writer you know.)

After the full committee agreed on a final draft, it was then presented to the Continental Congress. Because the Lee Resolution, notably the section containing the Declaration of  Independence, was so dramatic a turn holding such far-reaching effects, many delegates, just as today, were concerned about how their constituents back home would react. It took until July 2nd for twelve of the thirteen colonies to adopt the Declaration of Independence section within the Lee Resolution. New York was the only hold out, waiting until it's newly-elected New York Convention approved the section on July 9, 1776.

Independence, was so dramatic a turn holding such far-reaching effects, many delegates, just as today, were concerned about how their constituents back home would react. It took until July 2nd for twelve of the thirteen colonies to adopt the Declaration of Independence section within the Lee Resolution. New York was the only hold out, waiting until it's newly-elected New York Convention approved the section on July 9, 1776.

After the July 2nd adoption, Congress' revision process took only July 3rd and most of July 4th. All in all, the entire process, from Lee's Resolution of June 7 to the July 4th adoption, seems pretty timely by modern government standards. In the end, even with the various alterations and modifications, the Declaration is still, in soul and in practicality, Jefferson's creation.

With Jefferson's oversight, John Dunlap, official printer to the Congress, printed the first copies on July 5th. One copy was attached to Congress' July 4th "rough journal" notes of the day and dozens more were messengered up and down the colonies to state assemblies, conventions and commanding officers of Continental troops. These originals contained only two signatures: John Hancock, president of the Second Continental Congress and Charles Thomson, secretary. Above those signatures read the words "Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress". Today, there are twenty-six known, surviving copies. Commonly referred to as the Dunlap Broadsides, there are twenty-one in American institutions, two in British institutions and three owned by private individuals.

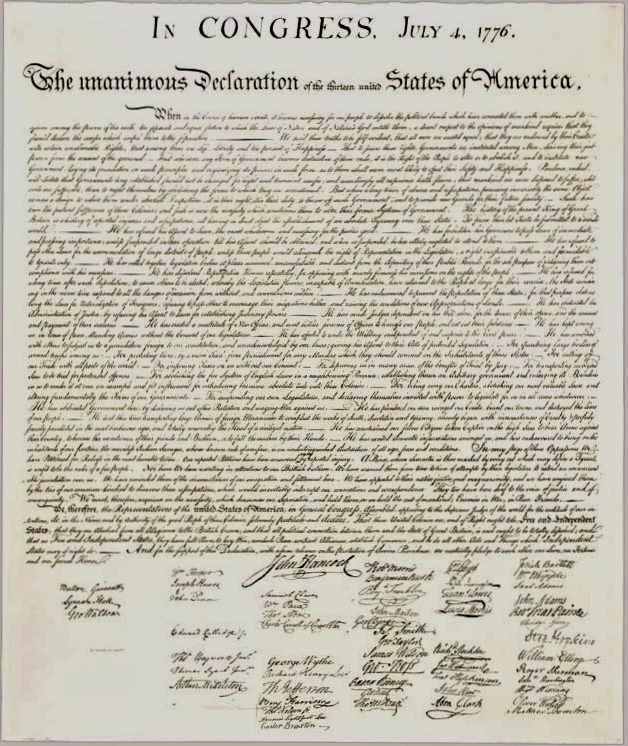

July 19th, 1776, Congress ordered the new Declaration of Independence to be "engrossed" on parchment, meaning to copy an official document in a larger type, and give it a new title: The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America. It was also ordered "that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress."

On August 2, 1776, president John Hancock signed the engrossed copy first with his notable, large, flourished signature: so well-known that even today John Hancock is synonymous with a signature. Those delegates in attendance that muggy, Philly, August day signed under Hancock, in order of colony geography, starting with the northernmost New Hampshire and ending with the southernmost Georgia. Eventually, fifty-six delegates would sign the Declaration of Independence. Of the late signers, Matthew Thornton of New Hampshire was unable to sign with his fellow Hampsherians due to a lack of space. Ironically, Robert R. Livingston of New York, one of the original, five committee members serving with Jefferson, Adams, Franklin and Sherman, never did sign.

When the sun would finally set on the Revolutionary War, in the late-summer of 1783, the Virginia Assembly would call a convention in the relatively new capital city of Richmond (having moved from Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780). The purpose? To draft a Fundamental Constitution for the Commonwealth of Virginia. It would begin with the following: ... that the government of Great Britain, with which the American States were not long since connected, assumed over them an authority unwarrantable and oppressive; that they endeavoured to enforce this authority by arms, and that the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode island [sic], Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, considering resistance, with all its train of horrors, as a lesser evil than abject submission, closed in the appeal to arms.

Celebrating the Fourth with fanfare and spectacle began as early as its very adoption day when church bells rang out and the brethren of Philadelphia and elsewhere alighted fireworks and merrymaking to mark the symbolic funeral of King George III, simultaneously burning him in effigy in town squares up and down the East Coast whilst imbibing great quantities of beer and wine.

In a letter from John Adams to his dear wife Abigail, dated July 3, 1776, he wrote the following:

The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.

Today, we love the Brits; they're, like, our BFF country. We're even all aflutter awaiting the new, royal bébé of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge! (Royal watchers say July 13th.) Still, America, eat your Boca Burgers and Snausages, sip your Pinot Grigio and dip your prettily painted toes in the cool waters of America's beaches and pools; but respect and reflect on what it took to get there.